DESCRIPTION

Gunshot residue analysis (GRA) is a chemical technique under firearm forensics that attempts to identify heavy metals particles that contaminates the skin of subjects believed to occur only when the subject has fired a gun recently.

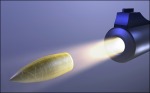

Gunshot residue is expelled as tiny particles from the barrel of gun when it is fired. The residue contains heavy metals barium, lead, and antimony.

ASTM International, developer of standards for forensic laboratories, has developed a guide for performing the technique that was approved in the United States in 2001. This states that gunshot residue particles are made only of lead, barium and antimony, but antimony and barium alone are “unique” to gunshot residue. The particles are identified using a scanning electron microscope and their composition analysed using energy-dispersive spectrometry.

Crime laboratory reports however provide a “most probably” result putting into question the reliability of this analysis in concluding that if such heavy metals were detected that the subject indeed fired the gun.

SPECIFIC TESTS

Paraffin Test. The paraffin test is one of the crudest of GRA methods that detects for nitrate residues. It uses liquified paraffin wax interlaced with gauze sheets applied on the hand skin to open up skin pores and collect chemicals inside the pores. When the wax cools, it forms a cast on which lab technicians apply either diphenylamine or diphenylbenzidine. Nitrates will cause blue dots to appear on the casts corresponding to the hand supposedly used to shoot. Reporting: The presence location of the blue dots recorded in drawings that technicians are required to make. Use in Courts: The report is treated as evidence that the suspect had fired a gun. In court, the administering technician testifies on the examination and presents the drawings with the interpretations made. Sources of False Negative Results: The gunpowder burns can be removed from the skin pores using warm vinegar. High temperature opens up the pores and forces out the gunpowder.

SCIENTIFIC STUDIES

However, studies as recent as 2005 have shown that a non-shooter can become contaminated by these heavy metals without firing a gun. Lubor Fojtásek and Tomás Kmjec at the Institute of Criminalistics in Prague, Czech Republic, fired test shots in a closed room and attempted to recover particles 2 metres away from the shooter. They detected “unique” particles up to 8 minutes after a shot was fired, suggesting that someone entering the scene after a shooting could have more particles on them than a shooter who runs away immediately (Forensic Science International, V153, P132). In fact, someone who entered the crime scene within this period can have more particles on them than the shooter who ran away immediately after the crime.

In a 2000 study, Debra Kowal and Steven Dowell at the Los Angeles county coroner’s department reported that it was also possible to be contaminated by police vehicles. Of 50 samples from the back seats of patrol cars, they found 45 contained particles “consistent” with GSR and four had “highly specific” GSR particles. What’s more, they showed that “highly specific” particles could be transferred from the hands of someone who had fired a gun to someone who had not.

Even worse, it is possible to pick up a so-called “unique” particle from an entirely different source. Industrial tools and fireworks are both capable of producing particles with a similar composition to GSR. And several studies have suggested that car mechanics are particularly at risk of being falsely accused, because some brake linings contain heavy metals and can form GSR-like particles at the temperatures reached during braking. In one recent study, Bruno Cardinetti and colleagues at the Scientific Investigation Unit of the Carabinieri (the Italian police force) in Rome found that composition alone was not enough to tell true GSR particles from particles formed in brake linings (Forensic Science International, vol 143, p 1).

HISTORY

In the 1990s, the courts accepted the presence of either two of these heavy metals from the gunshot residue as evidence of firing the firearm. However, today the courts require that all three metals must be present for gunshot residue be admitted as evidence on court.

History of Paraffin Testing

The validity of the paraffin test first came into question in the United States during the Warren Commission hearings of 1963 while investigating the assassination of late US president John F. Kennedy. FBI expert, Cortlandt Cunningham, testified that a laboratory experiment conducted by the agency determine the test is inconclusive.

In the study 17 men were made to fire five shots of a .38 cal. revolver using one hand only. After each string, both hands were subjected to paraffin testing. Results on eight of the test subjects showed negative or essentially negative results on both hands. This indicates that paraffin tests could not detect nitrates half the time. More surprisingly, three men showed positive results on the idle hand and negative on the firing hand. Four men tested positive on both hands, after having fired only with their right hand.

In the Philippines, paraffin testing has faced much scrutiny as well. Its unreliability as evidence was discussed in the SC’s conviction of Claudio Teehankee Jr on 6 Oct 1995 for the 1991 murder of Maureen Hultman, the killing of Roland John Chapman and the frustrated murder of Jussi Olavi Leino. At the lower court and the Court of Appeals, Teehankee capitalized on the negative paraffin test on him.

However the High Court ruled: “Scientific experts concur in the view that the paraffin test has ‘proved extremely unreliable in use. The only thing that it can definitely establish is the presence or absence of nitrates or nitrites on the hand. It cannot be established from this test alone that the source of the nitrates or nitrites was the discharge of a firearm.” It added: “We have also recognized several factors which may bring about the absence of gunpowder nitrates on the hands of a gunman, viz: when the assailant washes his hands after firing the gun, wears gloves at the time of the shooting, or if the direction of a strong wind is against the gunman at the time of firing.”

The Teehankee ruling revealed other sources of nitrate/nitrite contaminants such as firecrackers, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals and leguminous plants such as peas, beans, alfalfa, and tobacco.

National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) forensic chemist Leonora Vallado testified that excessive perspiration or washing of hands with the use of warm water or vinegar may remove gunpowder nitrates on the skin.

Much earlier court decisions proceeded on the same vein such as the People v. Ducay (1993), People v. Hubilo, (1993), People v. Pasiliao (1992), People v. Clamor (1991), People v. Talingdan (1990), and People v. Cajumocan (2004).

The High Court concluded that paraffin test is “of lesser consequence.”

TRENDS

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is more cautious in their protocol for GRA–“Because the possibility of secondary transfer exists, at least three unique particles must be detected…in order to report the subject/object/surface ‘as having been in an environment of gunshot primer residue’.” So a person could be named as a potential shooter in Baltimore, but given the benefit of the doubt by the FBI.

In the Philippines, the Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled paraffin test as inconclusive and cannot be used as the sole basis in determining whether the subject fired the firearm.

SOURCES

Mejia, Robin: “Why we can’t rely on firearm forensics,” New Scientist, 23 Nov 2005

KNR: “SC finds limited value in paraffin tests,” Sun Star Cebu, 19 Apr 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.